TABLE OF CONTENTS

Foreword

Introduction

Historical background

Analysis of Rumania’s nationality policy

1. Soviet influence on post-W.W. II Rumanian nationality policy

a) The Sovietization of Rumanian nationality policy

b) The reassertion of Rumanian nationalism: a reaction to Soviet influence

2. The nationality policy of the Ceausescu regime

a) The intensification of nationalism

b) Cultural discrimination

c) Socio-economic discrimination

d) Political discrimination

e) Statistical discrimination

f) The Rumanian propaganda campaign

g) The effects of Rumanian nationality policy

3. Determining factors in Rumanian nationality policy

a) Legitimacy

b) Historical factors - territorial integrity

c) Hungarian-Rumanian relations and the nationality question: the Hungarian position relative to the Transylvanian Question

d) The Soviet-Hungarian-Rumanian triangle

e) Political and ideological factors: legitimization through nationalism

f) Economic factors

g) Official Rumanian history: policy justification

4. The Hungarian-Rumanian conflict and the anti-Hungarian bias

a) Origins of the Hungarian-Rumanian conflict

b) Anti-Hungarian bias

The legal status of the Transylvanian Hungarian minority

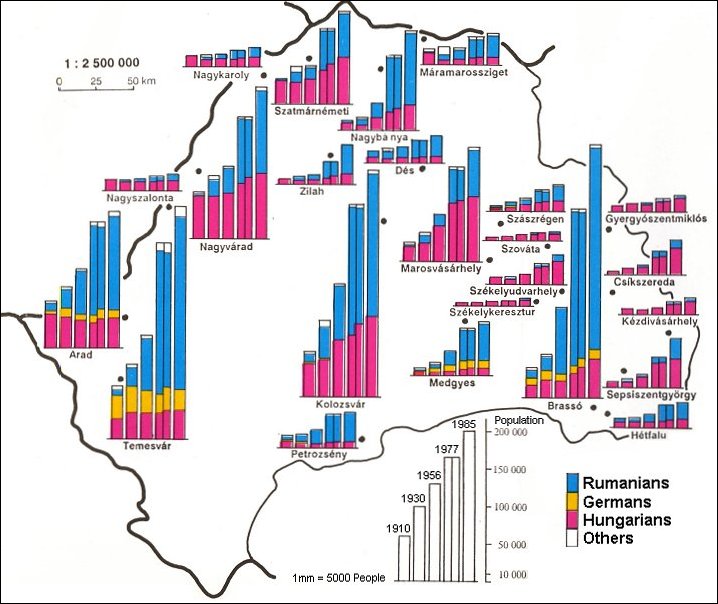

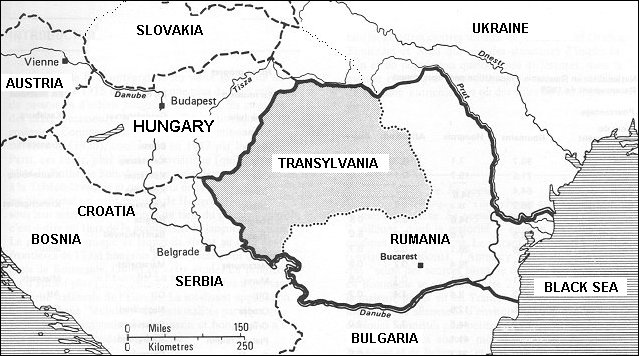

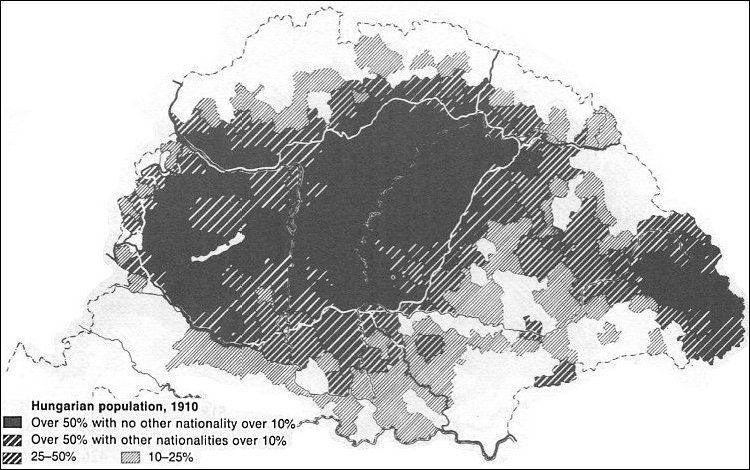

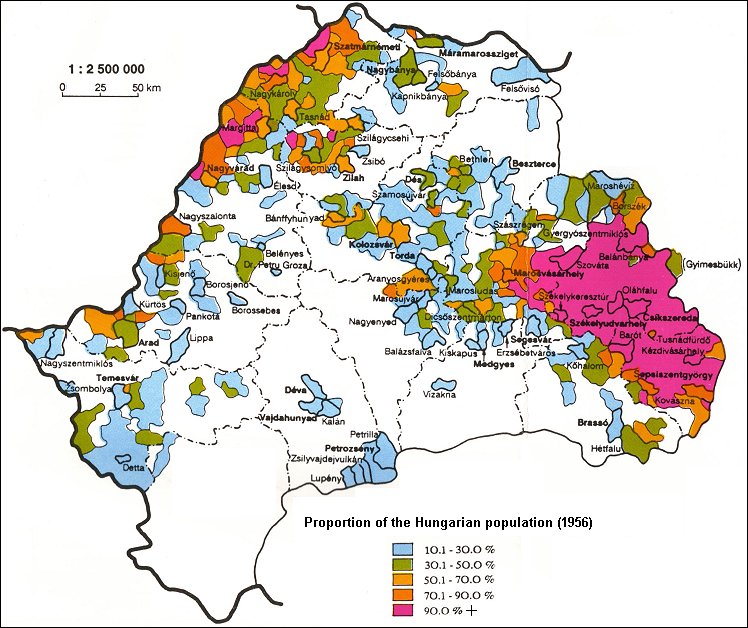

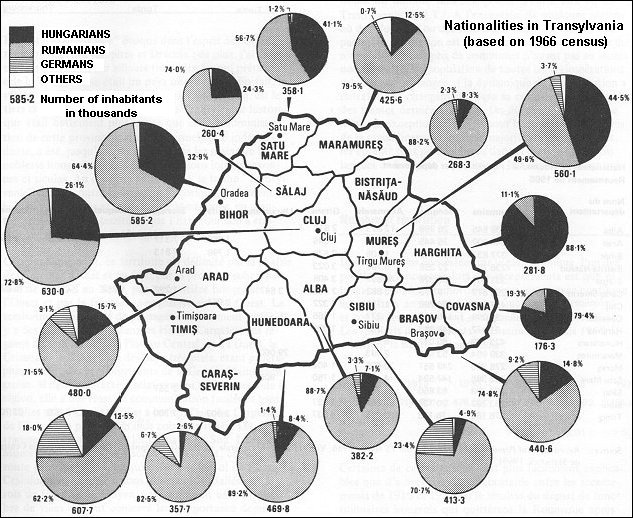

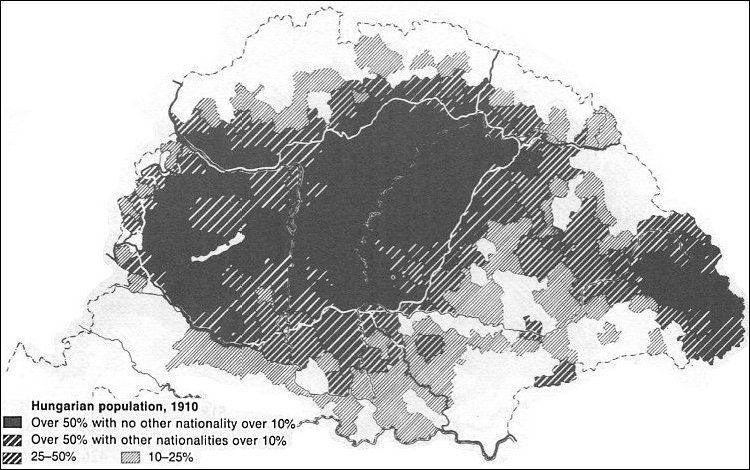

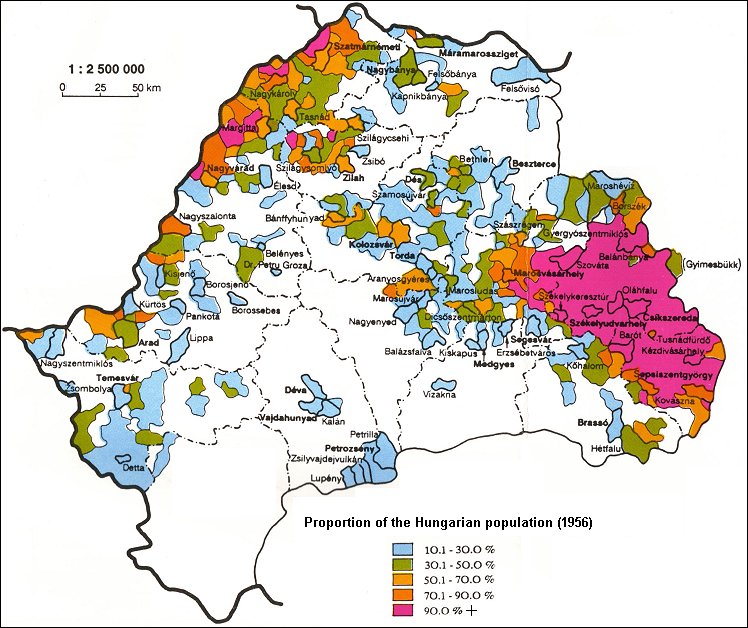

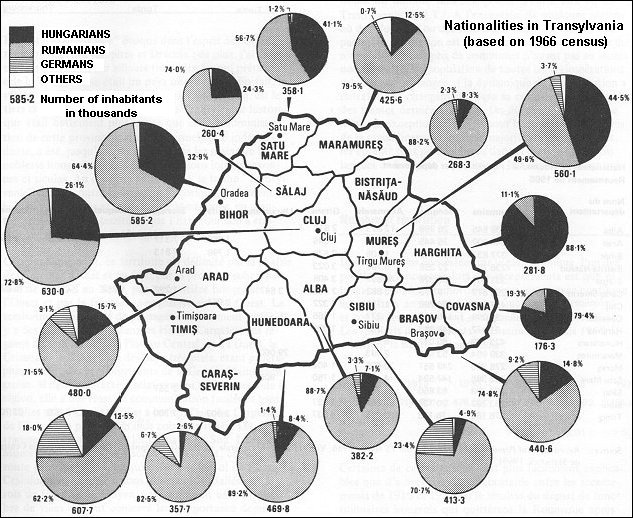

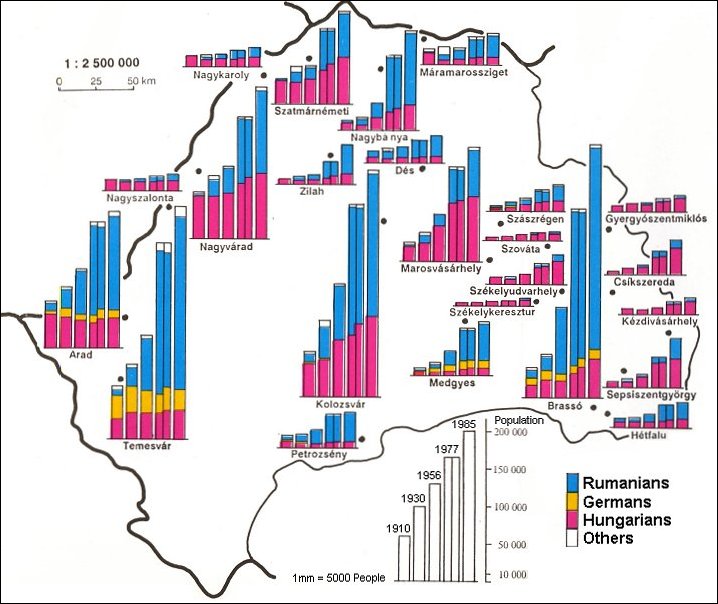

Appendix A - Transylvanian demographic trends

Appendix B - Tables and maps

Conclusion

Bibliography

FOREWORD

The objective of this study is the analysis of

the factors determining the present Rumanian regime's discriminatory treatment

of the approximatively 2.5 million Hungarians of Transylvania. Although the

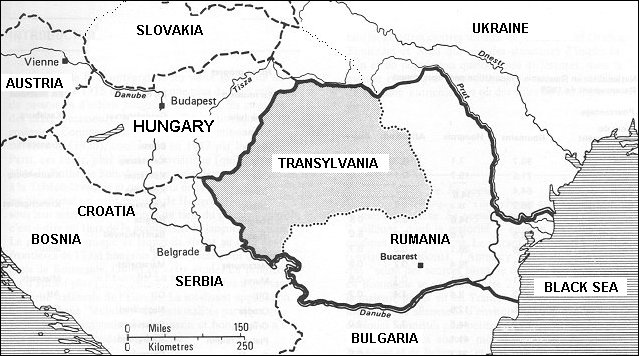

Hungarian territories annexed by Rumania are generally designated under the

name of Transylvania, the historical principality of Transylvania comprises

only about half of those annexed territories. In the present study however, the

generally accepted use of the name Transylvania will be kept, that is all the

Hungarian territories annexed by Rumania after the two World Wars will be

included under this designation. It should also be noted that there are other

Hungarians living in parts of Rumania, outside of Transylvania, who are subject

to treatment similar to that of the Transylvanian Hungarians.

The present Rumanian regime promotes a

nationalistic Rumanian historical version in order to justify its

discriminatory nationality policy towards the Transylvanian Hungarians, thus

seeking legitimation through nationalism based on a biased historical interpretation

and directed against the Hungarians in particular. The problem of the

repressive treatment of the Transylvanian Hungarians by Rumania raises a

relatively little examined question: the falsification and distortion of

historical facts for ideological or political purposes. This phenomenon is not

unique to the Transylvanian Problem. It is a characteristic of many cases where

one group ( nation, race, religious sect, political organization, etc...) seeks

to dominate, exploit, or even exterminate another group, proclaiming its own

superiority and the other's inferiority, attempting to impose its culture,

religion, or political system on others, often resorting to propaganda using

pseudo-historical or pseudo-scientific arguments to justify such imperialistic

policies. The Transylvanian Problem represents therefore an aspect of a much

larger and complex question which overlaps and combines the fields of history

and politics, and which may not have received the attention it deserves, due to

the artificial separation of these two disciplines.

The problem presently under study centers upon

what is often referred to as the Transylvanian Problem, which is the source of

conflict and tension between Hungary and Rumania. The history of Transylvania

is an integral part of Hungarian history until the end of the First World War.

However, since the end of the XVIIIth c., the history of Transylvania is

increasingly dominated by the conflict between the Hungarians and the

Rumanians.

The two most important aspects of Transylvanian

history from the point of view of the present study are, firstly, the

chronological order of settlement in that region by various ethnic groups, and

secondly, the evolution of the relationship between the Hungarians and the

Rumanians. The importance of the first aspect lies in the fact that the

Hungarians and Rumanians have conflicting historical claims to Transylvania,

and the Rumanian regime uses its historical interpretation as justification for

its policy of forced assimilation against the Transylvanian Hungarians. The

second aspect is also important since the conflictual Hungarian-Rumanian

relationship is a contributing factor in Rumania's policy towards the Transylvanian Hungarians.

The repressive Rumanian policy of political,

legal, educational, and economic discrimination, of forced cultural

assimilation, of deportation, and propaganda campaigns against the Hungarians

is directly related to the official Rumanian historical version which seeks to

project a distorted and falsified image of the Hungarians. They are portrayed

as invading barbarians who are the enemies of the Rumanian people. They are

labeled as undesirable alien latecomers who threaten the security of Rumania

and who are also culturally inferior to the Rumanians. It is therefore assumed

that it is in the interest of the security of the Rumanian state to eliminate

this dangerous foreign element, assimilation being one option which, according

to the official Rumanian historical interpretation, is also beneficial for the

Hungarians since it raises their culture to a ‘higher (Rumanian) level'.

A typical illustration of how the official

Rumanian historical interpretation serves to justify the policy of assimilation

towards the Hungarian population is provided by the case of the Székelys and

the Csángós. Both are Hungarian ethnic groups, the former inhabiting

Transylvania, and the latter, Moldavia. According to the official Rumanian

historical version, these ethnic groups would be ‘Hungarianized' Rumanians

which must therefore be ‘de-Hungarianized' and ‘re-Rumanianized'. Any

opposition to or criticism of this policy from the part of Hungarians is

branded as ‘fascist' and ‘chauvinistic' by the Rumanian regime.

The Rumanian

regime exploits the fear of the possibility of territorial revision in favour

of Hungary, for which there is a historical precedent since Hungary recovered

temporarily part of Transylvania as a result of the 1940 Vienna Arbitration,

this threat being referred to as Hungarian ‘revanchism' and ‘revisionism’ by

the Rumanian regime. According to this interpretation, the presumed Hungarian

territorial claims against Rumania, which the latter considers to be

unjustified, would be further weakened if the Hungarian population of the

territories bordering on Hungary would be eliminated, either through

assimilation or deportation. Thus the Rumanianization of Transylvania is seen

and promoted as an essential policy aiming to secure Romania's hold on and

claim of historical right to those territories, while simultaneously

undermining the basis for any Hungarian claims to Transylvania.

The Hungarian state and the Hungarians of

Transylvania are therefore seen as posing a threat to the security and the

territorial integrity of the Rumanian state. Although the Rumanian regime uses

the threat of Hungarian revisionism as justification for its nationality

policy, this threat seems fictitious under the present conditions since there

is no irredentist movement in Transylvania and the post-WWII Hungarian regimes renounced all former territorial

claims.

Although human rights, including those which

provide for the preservation of an individual's ethnic identity, are recognized

and stated in the peace treaties ending the two World Wars, the UN charter, and

the Helsinki accord, which have been signed by Rumania, as well as in the

Rumanian constitution itself, the Transylvanian Hungarians are subjected to

considerable discrimination by the Rumanian authorities, in violation of their

clearly stated and supposedly garanteed human rights. The treatment of the

Hungarian ethnic group by the Rumanian regime has increased the tensions

between Hungary and Romania. Most major Western states as well as the former

Soviet Union have also criticized Rumania's nationality policy. Nevertheless,

the program of forced assimilation of the Transylvanian and Moldavian

Hungarians has been further intensified by the various Rumanian regimes,

despite their claims to the contrary in official publications and declarations.

There is a considerable discrepancy between claims and statements made for

foreign consumption, and actual implemented domestic policies. The actual

policies, which differ from official statements, indicate the real objective of

forced assimilation (cultural genocide, or ethnocide), and the methods

(cultural, political, economic, administrative) of Rumania's nationality policy

towards the Hungarians.

The situation of the Transylvanian and Moldavian Hungarians seems to be continuously deteriorating under the present Rumanian regime:

- closing of Hungarian schools and universities

- restrictions on Hungarian language publications, press, and media

- banning of the use of the Hungarian language in public and in the administration

- banning of the use of Hungarian place names

- destruction of Hungarian villages and forced relocation

- socio-economic discrimination and political under-representation of the Hungarians

- restrictions on the Hungarians' freedom of movement and contact with friends and relatives living abroad

- harassment, arbitrary detention, torture, and assassination of important members of the Hungarian community by the state security services

- intimidation of Hungarians who do not declare themselves as Rumanians in the national census, and falsification of official statistics

INTRODUCTION

The purpose of

this study is to examine the factors which have determined Rumanian policies

towards ethnic Hungarians since Rumania took over Transylvania at the end of

the First World War. The principal thesis which is to be demonstrated is that

various Rumanian regimes, particularly the communist regime (especially under

Ceaucescu), sought legitimacy and justification for their policies, thereby

prompting the official exploitation and promotion of Rumanian nationalism and

generating a discriminatory policy of forced assimilation, or ethnocide,

directed against the ethnic minorities in Rumania, including those of Hungarian

nationality. The Rumanian nationality policy therefore served to legitimize the

regime in power and this policy was justified by a nationalistic official

version of history which also depicted the Hungarians as a threat to Rumanian

national security and territorial integrity. The objective of the nationality

policy of the "unitary national Rumanian State" was therefore:

“to "Roumanize Transylvania" -

that is to secure for the

Roumanian element a position of

unquestioned superiority

... the political enemy in chief

consists of the Magyar

minority, whose power, influence, and

numbers must be

weakened by all possible means.” (1)

The primary

factors, both internal and external to Rumania, which will be examined are of

historical, political, and ideological nature. The various nationality policy

implementation methods employed by the Rumanian authorities will be used as

indicators in order to establish a chronological trend and to correlate

Rumanian nationality policy with internal and external factors. In this manner,

the fundamental causes and consequences of this problem will be determined.

The problem of

the treatment of ethnic Hungarians in Rumania is the result of a complex set of

factors with wide-ranging historical and political ramifications. This problem,

otherwise referred to as the Transylvanian Question, is therefore part of a

wider geopolitical context of interrelated problems of similar nature. The Transylvanian

Question is the central issue of Hungarian-Rumanian relations. It is a

seemingly irreconcilable and highly controversial territorial and ethnic

dispute with deep historical roots, both sides claiming exclusive rights for

the possession of Transylvania, accusing each other of having oppressed their

co-nationals living there, and denying each other's accusations. Thus, with

each side blaming the other for causing this problem, no solution has yet been

reached.

The Transylvanian

Question, or more specifically the issue of the Hungarian minority's situation,

is itself part of the Hungarian Question which refers to the problem of the

Hungarian minorities living in the states surrounding Hungary. At present,

there are an estimated 4-5 million ethnic Hungarians (official censuses

recognize approximately 3 million only)(2), representing approximately one

third of all ethnic Hungarians inhabiting the Carpathian Basin, living outside

of Hungary in the neighboring states as a result of the border changes which

have taken place following the two world wars.

The estimated 2.4

to 3 million Hungarians in Rumania (3) constitute the largest Hungarian

minority and have also been subjected to extremely harsh conditions as a result

of Rumanian nationality policy which was reported as being the most oppressive

compared to the other states neighboring Hungary, although these states are

also engaged, to varying degrees, in discriminatory policies towards ethnic

Hungarians. The Hungarian Question thus involves Hungary with Slovakia,

Ukraine, Rumania, the former Yugoslav states, and Austria, and each of these

states is also involved in other domestic ethnic problems and/or territorial

disputes with other states.

The Hungarian

Question is the product of historical ethnic conflicts, otherwise known as the

Nationality Question, which centered upon the clashing national aspirations of

the Hungarian and non-Hungarian ethnic groups of the Middle Danubian Basin. To

a considerable extent, this nationality problem has been generated by

intervening major external powers seeking to dominate the region by exploiting

the potential antagonisms among its nationalities. This problem has been

perpetuated and exacerbated by the conflicting interpretations of the history

of these nationalities. The mutually contradicting and often politically

influenced historical versions tend to distort the view these nationalities

have of each other, thus sowing discord among them and preventing the

resolution of their conflicts.

The problem of the

Transylvanian and Moldavian Hungarians raises the conflicting issues of

nationalism and of minority rights with which international relations have been

increasingly preoccupied since the 19th c. Nationalism and nationality problems

have been at the root of most major wars and revolutions which have

fundamentally altered the political configuration of Europe during the past two

hundred years, opposing the concept of the unitary nation-state to the concept

of cultural, territorial, and administrative autonomy for ethnic minorities.

The principle of state sovereignty is also in contradiction with the declared

universality of human rights, which are assumed to include minority rights as

well, hence the ineffectiveness of international agreements and guarantees for

the protection of national minorities in a system of sovereign states.

The present study

is a multi-disciplinary approach to the issue of the Transylvanian Hungarians.

The historical, political, legal, socio-economic, demographic, cultural, and ideological

aspects of this problem will be examined in order to provide as comprehensive a

view as possible, which is essential for the accuracy of this type of analysis.

Due to the nature

of the problem which is to be analyzed, the historical dimension seems to

occupy a preponderant role among the determining factors of the Transylvanian

Question. Thus, the historical background is of great importance for the

understanding of this problem and will examine the roots of the

Transylvanian

Question, focusing on Hungary's loss of Transylvania to Rumania, as this event

provides a unique insight into the origins of this problem and the factors

determining Rumanian nationality policy towards ethnic Hungarians.

Following the

historical background, the present study will then proceed with the analysis of

Rumanian nationality policy towards ethnic Hungarians. This analysis will

determine the objective and examine the methods of implementation of Rumanian

nationality policy in the cultural, socio-economic, political, and legal

fields, leading to the analysis of the factors determining this policy.

The international

and domestic legal status of the Transylvanian Hungarians will also be

examined, giving an account of the attempts to solve this problem through

formal legal measures, and of the reasons for their lack of success.

A demographic

section will also present statistical data in order to provide a picture of the

changing ethnic composition and distribution of Transylvania's population. This

change itself is an indicator of the historical roots of the Transylvanian

minority problem and of the Rumanian nationality policy.

By examining the

various aspects of the Transylvanian Hungarian minority problem, this thesis

will present a synthesis of the different positions relative to this problem.

Two main difficulties confront this task: the relative inaccessibility of

primary sources and of original documents (most of which are undisclosed

official records, and some may even have been destroyed) as well as the difficulty

in finding truly impartial expert opinions on the subject matter, be they

Hungarian, Rumanian, or "neutral" third party. Therefore, another

“obstacle to a fully documented study of minority problems in Transylvania is

the absence of sufficient reliable data.” (4)

With respect to

the question of source reliability, it should be pointed out that documents

published in Hungary or Rumania cannot be attributed with the same level of

objectivity and accuracy as some independent Western scholarly sources, due to

political and ideological factors. This seems to be particularly the case of

documents originating from Rumania, as they are characterized by

“a lack of credible statistical

information as well as

an overabundance of biased propaganda.”

(5)

Certain

designations used in this research paper require some clarification. The

geographical name of Transylvania, as it is most commonly understood today,

refers to all the territories annexed by Rumania from Hungary after W.W. I (103

903 km2)(6). These territories include historical Transylvania itself (57 804

km2)(7), and in addition, parts of other former Hungarian territories known as

Máramaros (Maramures), Szatmár (Satu Mare), Kőrös Vidék (Crisana), and the

Bánság (Banat). Transylvania will therefore be referred to in its present wider

geographical extent, unless otherwise specified. The name

"Transylvania" is the Latin translation of the original Hungarian

name "Erdély" from which the Rumanian name "Ardeal" is also

derived (8).

The name of

"Rumania" and the term "Rumanian" will be used rather than

"Romania" and "Romanian", except in direct quotations where

it is spelled with an "o" or "ou" instead of a

"u". Both "Rumania" and "Romania" are presently

in use, although "Rumania" represents the original version which has

been gradually displaced by the official "Romania" version. Prior to

the creation of the Rumanian state in 1859, the Rumanians referred to

themselves as "Rumini" (9).

Two divergent

historical conceptions underly the two different spellings. The name

"Romania" is based on the Daco-Roman theory of the origin of the

Rumanians (10), whereas "Rumania" is based on the more widely

accepted view that the Rumanians originate from the Balkans, "Rum"

being the designation given by the Turks to the Balkans (11). The

"Rumanian" designation itself has only been used since the 19th c.,

prior to that, the Rumanians were known as "Vlachs" or

"Wallachians" ("Oláh" in Hungarian)(12).

The origin and

the relationship of the "Hungarian" and "Magyar"

designations should also be clarified in order to avoid certain confusions. The

term "Hungar", from which the "Hungarian" designation is

derived, is a collective ethnic name meaning Hun people or tribe (13). Each

Hunnic tribe and tribal federation had a specific name: Kuman, Pecheneg,

Magyar, Bulgar, Avar, Khazar, etc... These names became more widely known after

the breakup of the political unity of the Huns, following Atilla's death in 453

A.D. Thus, the Székelys of Eastern Transylvania (who were there before the

Magyars)(14) and the Moldavian Csángós are also Hungarian ethnic groups, as

well as the Magyars themselves, although Rumanian historiography has claimed

that the Székelys and Csángós were "Hungarianized" Rumanians, as a

justification for the policy of forced assimilation (15).

Therefore,

Rumanian nationality policy towards ethnic Hungarians has been determined

essentially by the need for legitimization of the Rumanian state. This need for

legitimization was generated by historical, political, ideological, and

economic factors, which will be analyzed in the following chapters. In the

conclusions drawn from the analysis of these factors, a fundamental long-term

solution seems to be the revision of the distorted and mutually antagonistic

national historical perceptions of the peoples in question in order to help

resolve nationalistic rivalries. This would require decisions made at the

political level and the freedom for unbiased scientific historical research. A

possible key to the resolution of nationality problems seems to lie in the

newly emerging (or re-emerging) historical data which contradict the

established versions upon which the present ideologically biased national

identities and perceptions are based.

The position

taken in this study is that a defense of the case of the Transylvanian and

Moldavian Hungarians is

required in order to counterbalance the wide dissemination of anti-Hungarian

propaganda in the West by Rumanians and others, in which serious accusations

are directed against the Hungarians. The defense of this case will therefore

strive for an objective analysis of factual evidence and for the avoidance of

ideological bias.

NOTES

(1) MaCartney, C.

A., Hungary and her Successors, Oxford U. P., London, 1937, p. 285.

(2) David, Z., "Statistics:

The Hungarians and their Neighbors", in Borsody, S.,ed., The

Hungarians: A Divided Nation, Yale Center for International and Area

Studies, New Haven, 1988, p. 345.

(3) Amnesty

International, Romania, Amnesty International USA Publications, 1978, p.

35.

(4) International

Commission of Jurists, "The Hungarian Minority Problem in Rumania",

in Wagner, F. S., ed., Toward a New Central Europe, Danubian Press,

Astor, Fla., 1970, p. 327.

(5) Keefe, K. E.,

et al, Romania - A Country Study, The American University, Washington D.

C., 1979, p. v.

(6) Haraszti, E.,

The Ethnic History of Transylvania, Danubian Press, Astor, Fla., 1971,

p. 1.

(7) Ibid., p. 1.

(8) Ibid., p. 1.

(9) Cadzow, J.

F., et al, eds., Transylvania: The Roots of Ethnic Conflict, Kent State

U. P., Kent, Ohio, 1983, p. 4.

(10) Ibid., p. 4.

(11) Ibid., p. 5.

(12) Ibid., p. 5.

(13) Badiny, F.

J., ed., The Sumerian Wonder, School of Oriental Studies, University of

Salvador, Buenos Aires, 1974, p. 223.

Knatchbull, H., The

Political Evolution of the Hungarian Nation, Arno Press, New York, 1971, p.

4.

(14) Haraszti,

op. cit., pp. 35, 48.

Kopeczi, B., ed.,

Erdély Torténete, Akadémiai Kiado, Budapest, 1986, p. 292.

(15) MaCartney,

op. cit., p. 286.

Pascu, S., and

Stefanescu, S., eds., Un jeu dangereux: la falsification de l'histoire,

Éditions scientifiques et encyclopédiques, Bucarest, 1987, p. 244.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

The importance of

the study of the Transylvanian Question's historical background lies in that it

demonstrates the origin and the role of the key factors which have determined

Rumanian nationality policy: the concern over the legitimacy and the permanence

of Rumanian territorial possessions, the interests and policies of major powers

relative to the area concerned, and the dissemination of anti-Hungarian

propaganda, which had a definite impact on the situation of the Hungarian

minorities.

The problem of

the Hungarian minorities was created by the Treaty of Trianon of June 4, 1920,

just as numerous other minority problems were created by the post-W. W. I

settlements imposed by the victorious Entente Powers. One of the critical

factors contributing to the plight of the ethnic minorities was that the

implementation of the minority rights protection clauses of the Peace Treaties

was inadequately guaranteed by the Entente Powers. As a result of the Treaty of

Trianon, Hungary lost 72% of its territory and 64% of its population (1), and

one third of the entire Magyar population was forced under foreign rule (2).

Therefore, the conditions imposed upon Hungary after W. W. I were by far

harsher in both relative and absolute terms than those imposed upon any other

state (3).

The terms of the

Treaty of Trianon were, however, largely determined by diplomatic events

leading up to and during the war, as well as by military events following it.

There is conclusive evidence that plans for the annexation of Hungarian

territories were envisaged well before the outbreak of the First World War by

the states which benefited from the partition of Hungary (4). The expansionist

aims of the Czechs, Serbia, and Rumania were manifested by the promotion of

separatist movements among the nationalities of Hungary (5) and by conducting a

highly publicized propaganda campaign in the West, with the collaboration of

certain influential personalities such as R. W. Seton-Watson (6), in order to

popularize their cause and to gain acceptance and support for their territorial

claims against Austria-Hungary:

“[Wickham] Steed, as the foreign policy

editor of the

Times, and Seton-Watson as the editor of New Europe...

used the press as weapons, often

arbitrarily and with

biased arguments, on behalf of the

imperialist objec-

tives of the Entente: the maximum

territorial claims

of the Slavs and the Romanians... Steed,

Seton-Watson,

and the officials and specialists,

including journalists

and politicians... contributed a great

deal to the pro-

cess of dissolution, to the fermentation

within the Mo-

narchy. The new order in Central Europe,

and the new

boundaries can be regarded largely as

the fruits of their

work before and after 1914.” (7)

Thus, the

propaganda campaign before and during the war had a definite impact upon the

political restructuring of the Danubian region (8).

Major powers,

such as Russia, seized the opportunities presented by the emergence of new

nationalistic small states such as Rumania, and exploited the latter's

territorial ambitions in order to serve their own hegemonistic objectives (9).

As a result, the Entente Powers recognized and supported territorial claims by

Balkan states against Austria-Hungary even before W. W. I (10). Serbia and

Rumania also realized that the territories they sought could only be obtained

through the intervention of major powers. Thus, the Balkan states were not

merely the pawns of the major powers, but they also exploited the latter's

imperialistic rivalries:

“each national disturbance presented

some of the Great

powers with an opportunity to further

their own interests

at the expense of others. Each

nationality that succeeded

in its struggle for independence did so

with at least

the tacit support if not open assistance

of one of the

Great powers. Those like the Poles and

Hungarians, who

lacked a powerful patron were

unsuccessful.” (11)

During the war

itself, through secret agreements, Hungarian territories were promised by the

Entente Powers to their Balkan allies. On August 17, 1916, the secret Treaty of

Bucharest was signed between the Entente and Rumania (12). The treaty promised

the Hungarian territories East of the Tisza river to Rumania, which, in

exchange, could not conclude a separate peace treaty with the Central Powers,

as this would invalidate the Bucharest Treaty (13). Consequently, the Rumanians turned against their former ally,

Austria-Hungary, and on August 27 proceeded to invade Transylvania, declaring

war upon the Dual Monarchy only after the attack had begun (14). The Rumanians

based their declaration of war on the claim that Hungary was oppressing its

Rumanian minority (15). Nevertheless, the Central Powers mounted a successful

counter-offensive as a result of which Rumania was forced to sign the Peace

Treaty of Bucharest on May 7, 1918, thereby invalidating the 1916 Bucharest

Treaty with the Entente (16).

On November 3,

1918, Austria-Hungary concluded an Armistice at Padua with Italy which had

received the mandate and authorization to act on behalf of the Allied and

Associated Powers (17). On that day, there were no Allied forces on Hungarian

territory (18). The Armistice designated the existent frontiers of

Austria-Hungary as the demarcation lines for the Balkan and Eastern fronts.

This Armistice was thus valid for all Austro-Hungarian fronts and officially

put an end to all hostilities between Austria-Hungary and the Allied and

Associated Powers (19). However, on November 4, 1918, the Supreme War Council

of the Allies unilaterally cancelled the Padua Armistice without the knowledge

and consent of the Austro-Hungarian

authorities on the grounds that one of the contracting parties to the

Armistice, Austria-Hungary, had ceased to exist. However, this argument had no

validity since the new Hungarian government had also accepted the terms of the

Padua Armistice (20).

Because at that

time Germany was still at war, the presence of German troops in Hungary

prompted the Allies to invade (21). These circumstances proved favorable for

the territorial claims of the Czechs, Serbians, and Rumanians. On November 13,

1918, the Allies concluded the

Belgrade Military Convention with Hungary in order to occupy certain Southern

and Eastern parts of that country (22). This was meant only as a temporary

measure which was not supposed to change the Hungarian administration in the

occupied regions (23). However, the Czechs, Serbians, and Rumanians violated

the Belgrade Convention by occupying more territory than they were authorized

to and by replacing the local Hungarian administration by their own (24).

Hungarian sovereignty and territorial integrity were thus violated after that

state had concluded a legal agreement for the termination of the war. In this

respect, it is interesting to note that on January 24, 1919, the Supreme Allied

Council declared that its members were

“deeply disturbed by the news which

comes to them of

the many instances in which armed force

is being made

use of, in many parts of Europe to gain

possession of

territory, the rightful claim to which

the Peace Con-

ference is to be asked to determine.

They deem it their

duty to utter a solemn warning that

possession gained

by force will seriously prejudice the

claims of those

who use such means. It will create the

presumption

that those who employ force doubt the

justice and va-

lidity of their claim and purpose to

substitute pos-

session for proof of right and set up

sovereignty by

coercion rather than by racial or

national preference

and natural historical association.” (25)

Nevertheless, as

a result of the violation of the Padua Armistice by the Allies, large parts of

Hungary's territory remained under foreign occupation, and those territories

were subsequently annexed by the successor states - Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia,

Rumania.

Several factors

contributed to the extent of Hungary's losses after the war. Having fought on

Germany's side, Hungary was considered and treated as a defeated enemy power by

the Allies (26). Consequently, the successor states were given preferential

treatment regarding their claims against Hungary. The foreign invasion of

Hungary precipitated the economic and political collapse of that country which

had also demobilized its army following the Armistice, thereby facilitating the

advance of enemy troops into Hungarian territory. As a result of the ensuing

chaotic conditions, a coup installed the communist regime of Béla Kun, a turn

of events which prompted further Allied intervention in Hungary, resulting in

the occupation of Budapest by Rumanian troops (27), and causing losses

estimated at 6.5 billion Swiss Francs (28).

The other major

concern of the Allies, besides Germany, was the Russian Revolution of 1917 and

the resulting threat of the spread of Communism:

“The Allied decision to embrace

officially the "New

Europe" plan had a great deal to do

with the loss of

Russia as an ally following the

Bolshevik Revolution

in October 1917... exiles from

Austria-Hungary sudden-

ly became more precious than ever before

in the propa-

ganda war agaist the Central

Powers.”(29)

Hungary was thus

in a particularly unfavorable set of circumstances where its interests were

subordinated to the intervening interests of major powers, especially those of

France, which was taking an increasingly hegemonic role in East Central Europe.

It was under such circumstances that Rumania took over the Eastern part of

Hungary, including historical Transylvania, as a reward for Rumanian assistance

against the Russian Red Army (30).

Another factor

which determined the extent of Hungarian territorial losses to neighboring

states such as Rumania, was the general lack of knowledge or interest among

Western statesmen concerning facts pertaining to Central and Eastern Europe,

combined with the particularly unfavorable image of Hungary created by the

propaganda campaigns of the successor states:

“reminiscing over Hungary's punishment

at the Paris

Peace Conference, the British diplomat

Harold Nicolson

noted: "I confess that I regarded,

and still regard,

that Turanian tribe with acute distaste.

Like their

cousins the Turks, they had destroyed

much and created

nothing." This Allied participant

at the Paris Peace

Conference did more than just express

his unflattering

opinion of the Hungarian people. He

captured the biased

political atmosphere of the

international setting in

which the historical Hungarian state met

its death.” (31)

It is therefore a

fact that the anti-Hungarian propaganda campaign

had a

considerable impact in terms of major power policy towards

Hungary. This has

also been a determining factor in the subsequent

treatment of the

Hungarian minorities.

The Treaty of

Trianon was not negotiated but merely imposed upon Hungary by force:

“what Trianon effected in actual fact

was quite simply

to endorse and legalize the occupations

by conquest,

achieved after the cessation of

hostilities, by the

armed forces of the so-called successor

states, in

stark violation of the armistice

agreements concluded

with the Allied and Associated Powers.”

(32)

The new borders

of Hungary were determined on the basis of claims and information presented by

the parties interested in the territorial dismemberment of Hungary. Hungary's

objections and demands for plebiscites were not taken into consideration at the

Peace Conference (33). In this manner, all ethnic, historical, geographical,

strategic, and economic considerations were applied discriminatorily in favor

of the successor states and to the detriment of Hungary in the determination of

the new frontiers (34).

The Hungarians

reluctantly agreed to sign the Treaty of Trianon, but only with the

understanding that the possibility of future revision was open (the so-called

Millerand letter) and that the acquisition of Hungarian territories by the

successor states was conditional upon the latter's compliance with the treaties

for the protection of national minorities (35). However, neither of these

guarantees were respected by the Allies and the successor states (36).

All this was

accomplished under the claim of serving justice and of realizing the ideals

proclaimed by the Allies (President W. Wilson's 14 Points for the

self-determination of the nationalities of Central and Eastern Europe).

However, the terms and the methods of implementation of the Treaty of Trianon

were in contradiction with the principles in the name of which the Allies

claimed to have fought:

“According to those principles

"peoples and provinces

are not to be bartered about from

sovereignty to sove-

reignty as if they were mere chattels

and pawns in a

game", but "every territorial

settlement involved must

be made in the interest and for the

benefit of the po-

pulation concerned", and also "upon the basis of free

acceptance of that settlement by the

people immediately

concerned".” (37)

As a result, 3.5

million Hungarians were placed against their will in a minority status in the

successor states (38). With only one exception where the outcome proved

favorable to Hungary (the

Sopron

plebiscite), the populations of the transferred territories were not consulted

as to which state they wished to belong to:

“The Treaty of Trianon violated the principle

of self-

determination... The peoples living on

the territories

severed from Hungary did not constitute

themselves

separate political units. No action on

the part of

these peoples can be regarded as

representing a wish

either to break away from Hungary, or to form indepen-

dent units. The so-called Rumanian,

Slovak and Serb

"National Councils" which were

set up in certain towns

had no justification whatever to

consider themselves

representative of the whole population

in the sense

that they had the right to decide

anything in the name

of that population. They had never been

elected; they

were self-constituted bodies.” (39)

The arguments

used in order to justify the Treaty of Trianon were that Hungary was

responsible for W. W. I. and that the millenial existence of the Hungarian

state represented in itself an injustice (40).

In the Dual

Monarchy, decisions relating to diplomatic and military matters were taken in

Vienna (41). In July 1914, the Hungarian government was firmly opposed to the

aggressive Habsburg policy towards Serbia (42). However, the Hungarian

objections were overruled by the Austrians, and Hungary was forced to accept

the decisions taken by the Habsburg government. The accusation that Hungary was

responsible for the war is therefore questionable:

“When the Crown Council decided for war,

Hungary had no

other course than to stand by her

obligations as an ally.

But if there is any nation whose responsible

leaders

were against the war, it is Hungary, and

the guilt of

engineering the war can certainly not be

laid to her

charge.” (43)

The

responsibility for W. W. I lies, in varying degrees, with the Habsburgs,

Russia, Germany, France, as well as Serbia, all of which pursued expansionist

or revanchist policies. Unlike such states as Rumania, Hungary had no

territorial ambitions. Territorial and hegemonic expansionism were among the

main causes of the war.

The other

accusation levelled against Hungary, that of the injustice of that state's

millenial existence, referred to the alleged thousand years of Hungarian

oppression of the national minorities. The implication of this accusation was

that the Carpathian Basin was already occupied by non-Hungarian populations

before the arrival of the Magyars, in 895 AD, who then supposedly subjugated

the previously settled inhabitants of the region. These claims of the successor

states represented the principal justifications of their territorial

acquisitions from Hungary.

These accusations

raise the Nationalities Question of pre-war Hungary, referring to the problems

between the Hungarian and non-Hungarian ethnic groups living in Hungary. The

origins of this problem are of particular importance to this study due to the

fact that this problem is still present under the form of the Hungarian

minorities in the states surrounding Hungary. It is therefore important to

examine the roots of these ethnic conflicts which, to a considerable extent,

have determined, among others, the Transylvanian Question, and have thus been

influential factors in Rumanian nationality policy.

Hungary's

neighbors claimed that they had inhabited the Carpathian Basin before the

Hungarians, and that therefore they had the historical right of possession of

its territories (44). The Rumanians, for their part, based their historical

claims on the so-called Daco-Roman continuity theory. This highly controversial

theory is still the subject of extremely divided opinions (45). While the

Hungarians maintain that the theory of Daco-Roman continuity is not

substantiated by any conclusive evidence (46),

“The Roumanians claim with passion that

their ancestors

have, on the contrary, inhabited

Transylvania, in un-

broken continuity, since its days of

Roman greatness,

having been merely ousted from their

heritage by the

barbaric, Asiatic Magyar intruders... We

do not know

for certain that Roumanians were in

Transylvania in the

year A.D. 1000... they cannot have been

either numerous

or important, neither can they have

possessed any orde-

red social or political society... nor

do we find any

record even of isolated groups...” (47)

In fact, the

historical claims of the successor states appear to be questionable:

“Up to the sixteenth century there is no

historical evi-

dence that alien races in any

considerable strength lived

next to the Magyars in the territory of

pre-war Hungary.

Apart from a moderate immigration of

German and Slovak

settlers and Wallach (Rumanian)

herdsmen, which began

slowly about the thirteenth century, the

population of

the country was overwhelmingly

Magyar.

The change in the ethnographical

composition of the

country from the original homogeneous

Magyar into a

heterogeneous one is... chiefly the

result of quite

recent immigration.” (48)

With respect to

the question of historical rights for territorial possession based on priority

of settlement, it is interesting to note that some of the most recent

researches into the ancient history of Europe have arrived to the conclusion

that before the appearance of the Indo-European peoples in Europe,

non-Indo-European peoples had already laid the foundations of European

civilization (49). These conclusions are supported by archeological finds, such

as that made in Transylvania in 1961 which indicates that the earliest

civilized settlements in the Carpathian Basin were of Mesopotamian Sumerian

origin (50).

During the 19th

c., British, French, and German researchers discovered the most ancient

civilization, that of the Sumerians, in Mesopotamia, and deciphered their

language, coming to the conclusion that the Sumerians were neither Semitic, nor

Indo-European (51). Comparative linguistic analysis has shown that the language

closest to Sumerian is Hungarian (52).

The evidence

therefore suggests that the ancestors of the present-day Hungarians had

established themselves in the Carpathian Basin as early as the Neolithic

period, well before the arrival of the Magyars in 895 AD, who represented the

last major link in the Scythian-Hun-Avar-Magyar continuity of Turanian peoples

which amalgamated with their ethno-linguistic relatives of Near Eastern origin

previously settled in the Danubian region. It should also be mentioned, in

connection with the Daco-Roman theory, that according to Roman sources, the

Dacians, who inhabited today's Transylvania, belonged to the family of Scythian

peoples, which also included the Huns, Avars, and Magyars (53).

However, during

the centuries of warfare and foreign occupation, starting with the Turkish

invasion and division of Hungary, a considerable shift in the ethnic

distribution of the population of the Carpathian Basin took place. While the

Hungarian population suffered comparatively greater losses, other ethnic groups

from the Balkans and Eastern Europe sought refuge or were settled by foreign

rulers in the depopulated areas of Hungary (54), thus considerably reducing the

proportion of Hungarians in Hungary, while the non-Hungarian population grew

more rapidly due to immigration and due to the fact that the areas they

inhabited were less exposed to devastation than those inhabited by Hungarians

(55). Transylvania was also affected by these trends as an increasing influx of

Rumanians took place, starting in the 13th c., as a result of the Mongol and

Turkish invasions of Eastern Europe and the Balkans (56).

The various

nationalities of the Carpathian Basin coexisted

peacefully until

the Habsburgs introduced their policy of inciting the various nationalities

settled in Hungary against the Hungarians:

“the policy of the Imperial Government

in Vienna,

which, in order to check Magyar

ambitions towards

freedom and independence, stirred up the

subject

nationalities and used them as a weapon

against

the Hungarians.” (57)

The Habsburgs

pursued a policy of divide and rule in Hungary since their take-over of that

country (58), starting with the partition of Hungary between the Habsburgs and

the Ottomans in the 16th c. This policy consisted essentially in settling large

numbers of foreigners in Hungary, in order to economically exploit and

politically divide Hungary to the Austrian Habsburgs's advantage:

“It is estimated that in the course of

the XVIIIth c.,

the Habsburgs installed or introduced in

Hungary some

400 000 Serbs, 1 200 000 Germans, and 1

500 000 Ruma-

nians and thus lowered the proportion of

Magyars in

the historic Kingdom, that had totalled

80 per cent

before the Turkish conquest, to less

than 40% by 1780.” (59)

In order to

incite the foreign nationalities against the Hungarians when the latter

repeatedly revolted against Austrian rule, the Habsburgs fostered the

development of the national self-consciousness of the non-Hungarian

nationalities and directed them against the Hungarians (60).

In this context,

the theory of Daco-Roman continuity was therefore a useful means of mobilizing

the Rumanians against the Hungarians:

“The principal center of this

["Dacian"] idea lay

across the Carpathians in Austrian

territory, where

Roman Catholic propaganda made

considerable progress

among Rumanian-speaking populations.

Official Austrian

support of Catholicism helped to forward

the movement...” (61)

“The aims of this ["Transylvanian

School"] movement

were not primarily scientific. The study

of Rumanian

history and language... was to support a

distinctly

Rumanian political struggle...” (62)

The objective of

this struggle was to re-establish the Rumanian nation "in the position of

pre-eminence" (63) which it was believed to have occupied in ancient

times. As a result, during the 18th and 19th c. Hungarian uprisings against the

Habsburgs, Rumanians settled in Hungary slaughtered entire Hungarian villages,

thereby contributing to the depopulation of Hungarian-inhabited areas and

increasing the Rumanian population's proportion in Transylvania and other parts

of Hungary (64). Due to the Rumanians's siding with the Habsburgs against the

Hungarians (65), the relations between these two nationalities deteriorated

considerably during the course of the 19th c.

The nationality

problem which was thus created had serious repercussions in the origins and

aftermath of the First World War. As a consequence of the nationality problem

in Hungary, certain non-Hungarians advanced the claim, mostly under foreign

influence (66), that the Hungarians have been oppressing the nationalities

which have supposedly inhabited the Carpathian Basin before the Hungarians who

subjugated them. These claims have been widely propagated since the latter part

of the 19th c., essentially in order to justify the territorial partition of

Hungary.

However, the

evidence seems to contradict these politically motivated historical claims:

“The administrative and political

organizations of

the Hungarian statehood, based on

autonomy and self-

government, was also the inherited legal

system of

the nomadic tribal life... Thus the

nomadic empires

were built on autonomy and

self-government, and the

concept of discrimination against

different racial

or language groups was unknown.

This principle of self-government and

tolerance to-

ward foreign groups, together with the

respect for the

liberty of others, prevailed in the same

way within the

Christian Hungarian Kingdom.” (67)

As a matter of

fact, it was in Transylvania that religious freedom was legalized for the first

time in Europe, in the 16th c. (68)

Furthermore the Hungarian state not only allowed the various ethnic

groups settled in Hungary to preserve their language and culture, but actually

contributed to their cultural and economic development:

“the Magyars lived for centuries in

complete harmony

with their co-nationals of other races

and always fos-

tered their national and cultural

development. Of this,

no better proof can be given than the fact

that all

the minorities of pre-war Hungary not

only maintained

their national characteristics, but

developed them and

grew in strength and wealth to an

incomparably greater

extent than did their kinsfolk in

Serbia, Wallachia, and

Moldavia.” (69)

Rumanian

historians have interpreted the peasant rebellions against the Hungarian feudal

regime as Rumanian national uprisings against Hungarian tyranny. This is a

misinterpretation since the Hungarian nobility was not exclusively of Hungarian

origin (70) and ethnic Hungarians constituted the bulk of the exploited

peasantry. It was therefore a case of feudal socio-economic conflict and not a

manifestation of conscious ethno-linguistic discrimination (71).

The Rumanians and

other nationalities have also claimed that they have been the victims of a

systematic campaign of forced Magyarization, or Hungarianization. In relation

to this claim, it should be noted that the so-called "Magyar

Chauvinism" for which Hungary was

criticized was a manifestation characterizing a small and unrepresentative

minority of the Hungarian population, namely the upper and middle classes

which, to a considerable extent, were composed of elements of non-Hungarian

origin (72). This important fact seems to have been overlooked by Hungary's

critics, such as R.W. Seton-Watson (Racial Problems in Hungary), who

made the mistake of accusing the Hungarian nation as a whole for the policies

of the reactionary oligarchy in power at the time. Hungary's ruling classes exploited

Hungarian nationalism for similar political reasons as later Rumanian

governments exploited Rumanian nationalism. It is also a fact that “the

Hungarian policy towards the racial minorities within pre-war Hungary was far

from being such as has been alleged in anti-Hungarian propaganda.” (73)

The evidence

seems to suggest that Hungarianization occurred essentially as a natural and

gradual assimilation of the immigrants into the more developed Hungarian

society, just as most immigrants from Europe tend to assimilate into the

dominant North American Anglo-Saxon culture:

“Moreover, some nations... do possess an

active power

of attraction which enables them easily

to absorb

alien elements, while others are

passive, yielding

readily to assimilation... few, if any

nations in

Europe possess this attraction in so

large a measure

as the Magyars... No other European

nation contains

so many recruits who are not at all

unwilling priso-

ners but, on the contrary, heart and

soul for their

adopted cause - indeed, its most

intolerant champions.

To deny that the

"Magyarization", whether in older or

in more recent times, often met with the

full approval

of the persons assimilated would... be

to misunder-

stand the position very seriously.” (74)

The policy of

Magyarization was a nation-building measure designed for the same purpose as

the cultural policies which led to the formation of nations such as the French

and the Americans through the assimilation of minorities and immigrants (75).

However, the French, the Americans, and other powerful nations were not

criticized as were the Hungarians for pursuing such policies (76). The aim of

the policy of Magyarization which was implemented in the second half of the

nineteenth century was the preservation of an endangered nation (77), the

continued existence of which was placed in doubt due to its numerical

inferiority (see p. 23) relative to the surrounding nationalities (78). The

integrity of the Hungarian state was also threatened:

“In the eighteenth century Hungary had

been extensively

colonized with non-Magyar elements; and

the [Habsburg]

Crown favoured these elements... The

granting of national

privileges to the immigrants was, in

fact, unconstitu-

tional, as it infringed the unitary

character of the

Hungarian constitution which each

newly-crowned Habsburg

swore to maintain, and threatened the

integrity of the

Hungarian kingdom.” (79)

Therefore,

through the policy of Magyarization, the Hungarian nation sought the

re-establishment of its ethnic homogeneity and of its political sovereignty

over the Hungarian kingdom which it had lost due to centuries of foreign rule

and occupation. The survival of an independent Hungarian national state was

therefore seen as impossible without the policy of Magyarization. However, in

the case of Hungary's ethnic minorities, the process of assimilation was

interrupted by the emergence of modern nationalism and by foreign intervention

which provoked and exploited conflicts between the Hungarians and the

non-Hungarians, leading to the territorial disintegration of Hungary, as a

result of which, approximately 4-5 million Hungarians are forced to live

outside of Hungary's present borders (80).

It therefore

appears that the political boundaries established by the Treaty of Trianon were

based on distorted and falsified information provided by the parties interested

in the partition of Hungary:

“the Trianon peacemaking was above all a

triumph of

propaganda.” (81)

The Allied powers

claimed as a reason for the partition of Hungary the inability of that state to

solve its nationality problem - this task was entrusted to the successor states

(82). Thus,

“Transylvania was transferred to

Rumania, on condition

that the latter "assumed full and

complete protection"

of the rights and liberties of the

Minorities.” (83)

However, instead

of solving the nationality problem of Hungary, the Treaty of Trianon

perpetuated it through the creation of new or enlarged multinational states

which contained large Hungarian minorities:

“Lloyd George himself pointed out in a

memorandum of

March 25, 1919, "There will never

be peace in South

Eastern Europe if every little state now

coming into

being is to have a large Magyar

irredenta within its

borders".” (84)

In many respects,

the nationality problem in the Danubian Basin deteriorated as a result of the

Treaty of Trianon :

“Mr. Vajda Voevode, [a former] Rumanian

Prime Minister,

said:"... More

Transylvanian-Rumanians were appointed

to the Hungarian High Court in Budapest

than are now

appointed in Bucarest. In Hungary there

were eight

high financial officials who were

Rumanians from Tran-

sylvania; to-day in Rumania there are

but two."...

Father Hlinka, the leader of the Slovak

Catholic Party,

wrote...: "For a thousand years we

did not suffer half

at the hands of the Hungarians that we

have had to

suffer in a few years at the hands of

the Czechs."...

Svetozar Pribitchevitch, former

Yugo-Slav Minister of

the Interior, [wrote]: "... If we

speak without bias,

we have to say that the Yugo-Slavs of

Austria and Hun-

gary had before the war more political freedom than

they had in Yugo-Slavia even before the

dictatorship..."

(85)

Following the

Rumanian invasion of Transylvania in November 1919, a Rumanian assembly

declared the union of Transylvania with Rumania at Gyulafehérvár (Alba Julia)

on December 1st (86). However, the legitimacy of the Alba Julia decision was

questionable due to the fact that the Rumanians did not represent the majority

of the population of the claimed territories since the non-Rumanians

represented 57% of the total population (87). Transylvania was therefore not

united with Rumania by the free will of its people, contrary to Rumanian claims

(88), but was conquered and annexed by military force (89). On January 19,

1919, over 30 000 Hungarians demonstrated in Kolozsvar (Cluj) against the

Rumanian occupation; Rumanian troops opened fire on the unarmed crowd, killing

over 100 and wounding over 1000 Hungarians (90).

The situation of

the Transylvanian Rumanians themselves did not improve with the creation of a

greater Rumanian national state:

“The Transylvanian Romanians, long

accustomed to consi-

derable autonomy and self-government

under Hungarian

rule, resented the imposition of central

control, es-

pecially under the administration of

officials from

Bucharest.” (91)

Even before the

annexation of Transylvania was recognized by the Treaty of Trianon, all

Hungarian language signs were being removed and replaced by Rumanian signs in

the occupied territories (92). As a result of the Rumanian annexation of

Transylvania, approximately 260 000 Hungarians fled to the remaining portion of

Hungary between 1920 and 1940 (93), while a large number of Rumanians migrated

to Transylvania (94). Thus, the Rumanian government began the implementation of

discriminatory measures against the ethnic minorities under its jurisdiction

and amounting to one third of the total population of Greater Rumania (95),

particularly against the Hungarians:

“The Hungarians became second class

citizens in Tran-

sylvania... Rumanian officials from

across the moun-

tains flooded the province...”(96)

Following the

annexation, large numbers of Transylvanian Hungarians became the victims of

illegal expropriations (97). In 1923, the Rumanian government introduced a land

reform in which land was taken from non-Rumanians, mainly Hungarians, and given

to Rumanians (98). In 1924, the Rumanian government imposed extra taxes on

Hungarian businesses still using the Hungarian language (99). In 1925, as a

result of the policy of Rumanianization, Hungarian schools were closed, and in

1926, censorship of Hungarian language publications was increased (100). In

1928, a Transylvanian delegation presented in Geneva to the League of Nations a

280-page report documenting 166 cases of Rumanian violations of the Minority

Treaty, but without effect (101). On October 15, 1934, a Hungarian Csango

revolt in the Gyimes Valley of Eastern Transylvania was crushed by the

authorities (102). In 1936, the extreme right-wing organization of the Iron

Guard conducted other violent acts against non-Rumanians, including Hungarians

(103). In 1938, royal dictatorship was imposed, and all political parties were

disbanded, including the organizations of the national minorities (104).

In 1940, Rumania

lost Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina to the Soviet Union, and the

German-Italian arbitration of the Second Vienna Award returned Northern and

Eastern Transylvania with 1.2 million Hungarians to Hungary, while the 600 000

Hungarians remaining under Rumanian rule were subjected to increasing abuses by

the Rumanian authorities (105). In 1944, siding with the Soviets, Rumania

reoccupied Northern and Eastern Transylvania, committing atrocities against the

Hungarian population and forcing the Soviets to intervene (106). However,

thousands of Hungarians were massacred and an estimated 200 000 were deported

to forced labor camps in Rumania, where most of them perished (107).

Following the

Second World War, the Rumanian authorities considered the Transylvanian

Hungarians as enemies of the state and treated them accordingly (108). As a

result, between 350 000 and 400 000 Hungarians were expropriated and expelled

from their homes, thus demographically and economically strengthening the

position of the Rumanians at the expense of the Transylvanian Hungarians (109).

It appears thus

that the policies of the Rumanian state towards ethnic Hungarians were, to a

considerable extent, determined by the conditions under which Rumania acquired

Hungarian territories. Having annexed Transylvania by force and under

questionable legal circumstances, the legitimacy of this acquisition was in

dispute. As a result, the territorial

integrity of Greater Rumania was not secure and the Hungarian minority was seen

as a threat to the security of the enlarged Rumanian state. The Rumanian

apprehensions concerning their territorial integrity were therefore the

principal motive for the treatment of the national minorities forced under

Rumanian rule. The situation of the Transylvanian Hungarians was

further

aggravated by the intervention of major powers such as France, Germany, and

Russia, which exploited and exacerbated the Hungarian-Rumanian conflict, and

also by the propaganda campaign directed against Hungary, which promoted

anti-Hungarian sentiments.

NOTES

(1) Homonnay, O.

J., Justice for Hungary 1920-1970, Hungarian Turul Society, West Hill,

Ont., 1970, p. 11.

(2) Borsody, S.,

ed., The Hungarians: A Divided Nation, Yale Center for International and

Area Studies, New Haven, 1988, p. xvii.

(3) MaCartney, C.

A., Hungary and her Successors, Oxford U. P., London, 1937, p. 1.

(4) Horvath, E., Transylvania

and the History of the Rumanians: A Reply to Professor R. W. Seton-Watson,

Sarkany Printing Co., Budapest, 1935, p. 75.

(5) Taylor, A. J.

P., The Struggle for Mastery in Europe 1848-1918, Oxford U. P., London,

1980, p. 190.

Horvath, E., op.

cit., pp. 74-75.

Horvath, E.,

"The Diplomatic History of the Treaty of Trianon", in Apponyi, A., et

al, Justice for Hungary, Longmans Green & Co. Ltd., London, 1928,

pp. 44-46.

MaCartney, C. A.,

Hungary - A Short History, Edinburgh University Press, 1962, pp.

201-202.

(6) Hanak, H., Great

Britain and Austria-Hungary During the First World War, Oxford U. P.,

London, 1962, p. 128.

Calder, K. J., Britain

and the Origins of the New Europe 1914-1918, Cambridge U. P., London, 1976,

pp. 8-10.

(7) Vigh, K.,

"The Causes and Consequences of Trianon: A Re-examination", in

Kiraly, B. K., et al, eds., Essays on World War I: Total War and Peacemaking

- A Case Study on Trianon, Brooklyn College Press, New York, 1982, p. 64.

(8) Hunyadi, I.,

"L'image de la Hongrie en Europe occidentale ŕ l'issue de la 1čre Guerre

mondiale", in Ayçoberry, P., et al, eds., Les conséquences des Traités

de Paix de 1919-1920 en Europe centrale et sud-orientale, Association des

Publications prčs les Universités de Strasbourg, Strasbourg, 1987, p. 175.

MaCartney, C. A.,

Hungary, Ernest Benn Ltd., London, 1934, p. 6.

(9) Calder, op.

cit., pp. 1-2.

(10) Pastor, P.,

"The Transylvanian Question in War and Revolution", in Cadzow, J. F.,

et al, eds., Transylvania: The Roots of Ethnic Conflict, Kent State U.

P., Kent, Ohio, 1983, p. 164.

Horvath, in

Apponyi, op. cit., p. 39.

(11) Calder, op.

cit., pp. 2-3.

(12) Pastor, in

Cadzow, op. cit., p. 166.

(13) Horvath, in

Apponyi, op. cit., p. 94.

(14) Pastor, in

Cadzow, op. cit., p. 166.

(15) Szasz, Z., The

Hungarian Minority in Roumanian Transylvania, The Richards Press, London,

1927, p. 20.

(16) Pastor, in

Cadzow, op. cit., p. 167.

(17) Horvath, in

Apponyi, op. cit., p. 88.

(18) Ibid., p.

80.

(19) Ibid., p.

82.

(20) Ibid., pp.

82-83.

(21) Pastor, in

Cadzow, op. cit., p. 169.

(22) Ibid., p.

169.

(23) Deak, F., Hungary

at the Paris Peace Conference, Columbia U. P., New York, 1942, p. 11.

(24) Horvath, in

Apponyi, op. cit., p. 89.

(25) Deak, op.

cit., p. 40.

(26)

Albrecht-Carrié, R., A Diplomatic History of Europe Since the Congress of

Vienna, Harper & Row, New York, 1973, p. 370.

(27) MaCartney,

C. A., Hungary and her Successors,

Oxford U. P., London, 1937, p. 39.

(28) Horvath, in

Apponyi, op. cit., p. 96.

(29) Borsody, S.,

"State- and Nation-Building in Central Europe: The Origins of the

Hungarian Problem", in Borsody, op. cit., p. 26.

(30) Czege, A.

W., ed., Documented Facts and Figures on Transylvania, Danubian Press,

Astor, Fla., 1977, p. 175.

(31) Borsody, op.

cit., pp. 26-27.

(32) Daruvar, Y.

de, The Tragic Fate of Hungary, Nemzetor, Munchen, 1974, pp. 169-170.

(33) Deak, op.

cit., p. 246.

Donald, R., The

Tragedy of Trianon, Thornton Butterworth Ltd., London, 1928, p. 19.

(34) Great

Britain, Parliament, House of Lords and House of Commons, The Hungarian

Question in the British Parliament, Grant Richards, London, 1933, pp.

442-443.

MaCartney, C. A.,

October Fifteenth: A History of Modern Hungary -1929-1945, Edinburgh U.

P., 1957, p. 4.

(35) Notes and

Aide-Memoires of the Hungarian Ministry of Foreign Affairs (1946), in Cadzow,

op. cit., p. 331.

(36) Horvath, in

Apponyi, op. cit., p.100.

Lukacs, G.,

"The Injustices of the Treaty of Trianon", in Apponyi, op. cit., p.

166.

(37) Great

Britain, op. cit., p. 442.

(38) Ibid., p. 8.

(39) Ibid., pp.

8, 444.

(40) Hanak, op.

cit., p. 34.

(41) Great

Britain, op. cit., p. 440.

(42) Ibid., p.

441.

(43) Ibid., p.

441.

(44) Pascu, S., A

History of Transylvania, Wayne State U. P., Detroit, 1982, p. 292.

(45)

Seton-Watson, R.-W., A History of the Roumanians, Archon Books, Hamden,

Conn., 1963, pp. 9-11.

(46) Haraszti,

E., Origin of the Rumanians, Danubian Press, Astor, Fla., 1977, pp. 8-9.

Stoicescu, N., The

Continuity of the Romanian People, Editura Stiintifica si Enciclopedica,

Bucarest, 1983, pp. 103-104.

(47) MaCartney, Hungary

and her Successors, op. cit., p. 256.

(48) Great

Britain, op. cit., pp. 433, 435.

(49) Paliga, S.,

"Thracian Terms for `township' and `fortress', and related

place-names", in World Archeology, Vol. 19, No. 1, 1986, pp. 26-29.

Tihany, L. C., A

History of Middle Europe, Rutgers U. P., New Brunswick, New Jersey, 1976,

p. 9.

(50)

Constantinescu, M., et al, Histoire de la Roumanie, Editions Horvath,

Paris, 1970, p. 23.

Childe, G. V., The

Danube in Prehistory, Oxford U. P., London, 1929, p. 205.

(51) Kramer, S.

N., The Sumerians, University of Chicago Press, 1963, p. 306.

Erdy, M., The

Sumerian Ural-Altaic Magyar Relationship - A History of Research,

Gilgamesh, New York, 1974, pp. 60, 78.

(52) Gosztony,

K., Dictionnaire d'étimologie sumérienne et grammaire comparée, Editions

E. de Boccard, Paris, 1975, p. 175.

(53) Czege, op.

cit., p. 11.

Illyés, E., Ethnic

Continuity in the Carpatho-Danubian Area, Harvard U. P., Cambridge, Mass.,

1988, p. 147.

(54) Haraszti,

E., The Ethnic History of Transylvania, Danubian Press, Astor, Fla.,

1971, pp. 55, 83.

(55) MaCartney,

op. cit., pp. 9-10.

(56) Ibid., p.

261.

MaCartney, Hungary

- A Short History, op. cit., pp. 116-121.

(57) Great

Britain, op. cit., p. 437.

(58) MaCartney,

op. cit., p. 145.

(59) Daruvar, op.

cit., p. 20.

(60) Halasz, Z., A

Short History of Hungary, Corvina Press, Budapest, 1975, p. 142.

(61) McNeill, W.

H., Europe's Steppe Frontier 1500-1800, University of Chicago Press,

1964, p. 208.

(62) Lote, L. L.,

ed., Transylvania and the Theory of Daco-Roman-Rumanian Continuity,

Committee of Transylvania Inc., Rochester, N. Y., 1980, pp. 11-12.

(63) Hitchins,

K., The Rumanian National Movement in Transylvania, 1780-1849, Harvard

U. P., Cambridge, Mass., 1969, p. 71.

(64) Haraszti,

op. cit., p. 105.

Seton-Watson, op.

cit., pp. 284-285.

(65) Hitchins,

op. cit., pp. 244-245.

(66) May, A. J., The

Hapsburg Monarchy 1867-1914, Harvard U. P., Cambridge, Mass., 1960, p. 265.

(67) Zathureczky,

G., Transylvania - Citadel of the West, Danubian Press, Astor, Fla.,

1967, pp. 14-15.

(68) Ibid., p.

23.

(69) Great

Britain, op. cit., pp. 437-438.

(70)

Seton-Watson, H., Nations and States - An Enquiry into the Origins of

Nations and the Politics of Nationalism, Westview Press, Boulder, Colorado,

1977, p. 157.

(71) MaCartney, Hungary

and her Successors, op. cit., pp. 256-257.

(72) MaCartney, Hungary

- A Short History, op. cit., pp. 189-192.

MaCartney, October

Fifteenth, op. cit., p. 15.

Sinor, D., History

of Hungary, Praeger, New York, 1966, p. 279.

Jaszi, O., The

Dissolution of the Habsburg Monarchy, University of Chicago Press, 1929,

pp. 324-326.

(73) Great

Britain, op. cit., p. 438.

(74) MaCartney, Hungary

and her Successors, op. cit., pp. 13-14.

(75) Jaszi, op.

cit., p. 328.

(76) Knatchbull,

H., The Political Evolution of the Hungarian Nation, Arno Press, New

York, 1971, pp. 300-301.

(77) MaCartney, Hungary

- A Short History, op. cit., p. 183.

(78) Herder, J.

G., Outlines of a Philosophy of the History of Man, Bergman Publishers,

New York, 1966, p. 476.

(79) MaCartney,

C. A., National States and National Minorities, Oxford U. P., London,

1934, pp. 114-115.

(80) MaCartney, Hungary

and her Successors, op. cit., pp. 9, 15, 36-37.

(81) Borsody, S.,

"Hungary's Road to Trianon: Peacemaking and Propaganda", in Kiraly,

op. cit., p. 27.

(82) Szasz, op.

cit., p. 20.

(83) Ibid., p.

20.

(84) Kertesz, S.

D., "The Consequences of World War I: The Effects on East Central

Europe", in Kiraly, op. cit., p. 47.

(85) Great

Britain, op. cit., pp. 438-439.

(86) Czege, op.

cit., p. 24.

Ceausescu, I.,

ed., War, Revolution, and Society in Romania - The Road to Independence,

Columbia U. P., New York, 1983, p. 270.

(87) Pastor, in Cadzow,

op. cit., p. 171.

(88)

Constantinescu, M., Pascu, S., eds., Unification of the Romanian National

State - The Union of Transylvania with Old Romania, Publishing House of the

Academy of the Socialist Republic of Romania, Bucharest, 1971, pp. 299-304.

(89) Szasz, op.

cit., p. 24.

(90) Czege, op.

cit., p. 24.

(91) Keefe, op.

cit., p. 19.

(92) Czege, op.

cit., p. 25.

(93) Cadzow, op.

cit., p. 337.

(94) Szasz, op.

cit., p. 62.

(95) Ibid., p.

49.

(96)

Seton-Watson, H., Eastern Europe Between the Wars, Archon Books, Hamden,

Conn., 1962, pp. 300-301.

(97) Deak, F., The

Hungarian-Rumanian Land Dispute, Columbia U. P., New York, 1928, p. 1.

(98) Cadzow, op.

cit., p. 29.

(99) MaCartney, Hungary

and her Successors, op. cit., p. 322.

(100) Czege, op.

cit., pp. 26-27.

(101) Cadzow, op.

cit., p. 29.

(102) Ibid., p.

30.

(103) Czege, op.

cit., p. 27.

(104) Cadzow, op.

cit., p. 30.

(105) Czege, op.

cit., pp. 27-28.

(106) Cadzow, op.

cit., p. 31.

(107) Czege, op.

cit., pp. 28-29.

(108) Cadzow, op.

cit., p. 316.

(109) Ibid., pp.

314-325.

ANALYSIS OF THE RUMANIAN COMMUNIST REGIME'S NATIONALITY POLICY

1. Soviet influence on post-W.W.II Rumanian nationality policy.

a) The Sovietization of Rumanian nationality policy.

The Soviet

military occupation of Rumania and subsequent political take-over at the end of

W.W.II effectively placed Rumania under Soviet control. This had a definite

impact upon Rumanian nationality policy affecting the ethnic minorities as the

entire political, economic, and social structure of the country was reorganized

according to the Soviet model (1). As a result, and in order to win over the

support of the national minorities for the communist regime, the minorities